Megan Cope

Melbourne

2017

Displayed 2017 at Art Gallery of New South Wales

Megan Cope

Born 1982, Brisbane. Lives and works Melbourne

Quandamooka, North-East region

Megan Cope employs a combination of traditional and contemporary materials and processes to explore the myths and methodologies of colonisation and the intricate relationship between the environment, geography and identity. Her work seeks to challenge constructs of time, our sense of place and the fabric of our society, which was formulated with the arrival of European colonisers and convicts.

Artist text

by Léuli Eshraghi

With the European invasion of sovereign First Nations territories in this part of Vasa Loloa, the Great Ocean, (1) came the political drive to eliminate Indigenous governments, villages, knowledges and peoples. These assimilation and dispossession policies, located in unceded lands and waters ecologically altered through capitalist exploit for the benefit of the majority European diaspora, acutely inform reality today.

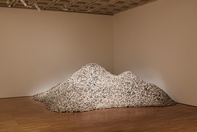

Quandamooka Nation artist Megan Cope addresses the violence, seen and unseen, of colonisation throughout vast territories. The third in an ongoing series, RE FORMATION part 3 (Dubbagullee) (2017) is the largest shell monument that Cope has produced to date. While smaller monuments have appeared almost directly out of the gallery floor and walls, this new monument echoes the grandeur and enormity of the vast structures that were shaped by thousands of years of Ancestors fulfilling ceremonial–political practices.

It is a haunting presence, created by slowly caring for the memory of Ancestors and healing the multiple absences, through the precise repetition in hand-making the layered forms of black sand, copper slag and cement oyster shells. An echo on the wind, a cultural memory recalled into being, standing in the place of countless villages and ceremonial sites that were obliterated across coastal First Nations territories, sacred sites of intergenerational histories, reaching far along the shores and high into the skies.

The deliberate burning of shell monuments thousands of years old, holding in their structure earth, shells, Ancestors and belongings, cannot be understated as a repeated act of cultural genocide, in Australia as in Aotearoa New Zealand, Hawai‘i, Canada and the US. The same brutality lies in the forcible displacement of First Nations peoples put to work as underpaid or unpaid labour in constructing ‘Brisbane’ along the river Maiwar and other nearby townships. (2)

In ‘Sydney’, massive Indigenous shell monuments and village sites that existed across Eora Nation territory were subsequently destroyed and built over by British colonists. (3) The Old Norse term ‘midden’ refers to a dung heap, a refuse heap near a dwelling or prehistoric pile of bones and shells. Here is the radical difference in perspective: the rapid, extensive removal of Ancestors and belongings from villages and ceremonial sites through burning for lime was core to the settler colonial myth-making in normalising White Australia as a natural outpost of European knowledges and practices.

Glistening in the light, Cope’s shell monument draws the viewer into what David Garneau describes as ‘sovereign Indigenous display territory’, non-colonial spaces of Indigenous life autonomous of western frameworks of being and knowing. (4) Rather than presenting us with a performance of ongoing First Nations pain and trauma, Cope resists the narratives of manifest destiny and terra nullius. Here, Indigenous sovereignty is actual healing: not a metaphorical return to customary concepts predating European invasion and genocide but an intellectual, spiritual, linguistic and ceremonial–political return to kunjiel, to jagan. (5)

RE FORMATION part 3 (Dubbagullee) charts a restoration of land-based practices that will bring the right people to see Quandamooka jagan marumba, (6) to see First Nations living practices in the present and future tenses.

Notes

(1) In the Sāmoan language Vasa Loloa is the Great Ocean.

(2) Elisabeth Gondwe, ‘North Stradbroke Island Historical Museum’, in Vivian Ziherl (ed.), Frontier imaginaries: edition no. 1, FRONTIER, Institute of Modern Art and QUT Art Museum, Mianjin Brisbane, 2016, p.175.

(3) Peter Meyers, ‘The third city: Sydney’s original monuments and a possible new metropolis’, ArchitectureAU, 1 January 2000, www.architectureau.com/articles/the-third-city/.

(4) David Garneau, ‘Imaginary spaces of conciliation and reconciliation’, West Coast Line, iss.74, Summer 2012, p.37.

(5) In the Jandai language jagan is land and sea Country and kunjiel means ceremony.

(6) In the Jandai language Quandamooka jagan marumba translates as Quandamooka Country is beautiful.