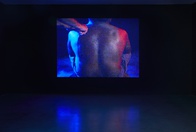

Curtis Taylor & Ishmael Marika

Perth. Martu, Western Desert region Yirrkala, Northern Territory. Rirratjingu, Arnhem region

2019

Displayed 2019 at Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

Curtis Taylor & Ishmael Marika

Curtis Taylor

Born 1989, Broome, Western Australia. Lives and works Perth. Martu, Western Desert region

Ishmael Marika

Born 1991, Nhulunbuy, Northern Territory. Lives and works Yirrkala, Northern Territory. Rirratjingu, Arnhem region

Curtis Taylor is a Martu artist whose practice spans sculptural installation, painting and film. His work investigates narratives around identity, language and cultural frameworks through the lens of ritual, performance and traditional cultural practices. In his film work he creates confronting virtual realities that shift the paradigm of film noir. Ishmael Marika is a Yolngu filmmaker, director and producer. He is currently the Creative Director of the Mulka Project at Yirrkala, and seeks to promote the cultural, visual and performative practices of Yolngu artists through documentaries and other forms of film media.

Photograph: Rebecca Mansell

Artist text

by Liz Nowell

In 2014, filmmaker Ishmael Marika premiered his short film Galka at Garma Festival, an annual festival of Yolngu culture held in North-East Arnhem Land. Inspired by a nightmare Ishmael couldn’t shake, Galka is a spine-chilling story about a young boy who meets with foul play while hunting out bush.

At the same time, over 3,000 km away in the Western Desert, Martu man Curtis Taylor was finishing his own narrative-based short, titled Mamu. A cautionary tale, Mamu follows the story of Bob, who angers the spirits after posting photos of sacred cave paintings on his Facebook page.

Although the artists had never met, these analogous stories might suggest that it was in fact inevitable and necessary that Curtis Taylor’s and Ishmael Marika’s paths cross.

Curtis and Ishmael did meet, in Djarindjin at the 2014 national Remote Indigenous Media Festival. The connection was instant and similarities undeniable – both studied at university in regional centres; both came from a proud history of political activism; both exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, at the same time; and both shared a passion for their culture, filmmaking and the horror genre. The parallels were as eerie as their short films.

Over the following 18 months, despite being separated by long stretches of changing Country, Curtis and Ishmael visited one another several times, learning about the other’s culture, family and lore. As their relationship strengthened, Curtis and Ishmael accepted an invitation to collaborate, creating new works for the exhibition In Cahoots: Artists Collaborate across Country, which was presented at Fremantle Arts Centre in 2017–18. Through their friendship, conversation and mutual support, Curtis and Ishmael extended their practice beyond film, creating sculptural installations to sit alongside new video works. The National 2019 marks the artists’ second collaboration and the strengthening of this artistic partnership.

Informed by Aboriginal culture and western cinematic conventions, Curtis and Ishmael create immersive film-based installations that explore themes of life, death, ritual and healing. In an industry dominated by white auteurs, the collaborative work of Curtis and Ishmael offers a powerful counterpoint to the many racist tropes and ill-informed representations that exist in mainstream cinema. By expressing culturally specific practices through a globally accessible and understood medium, Curtis and Ishmael have established an artistic language that reflects Yolngu and Martu people but, significantly, can be understood universally.

Both Curtis and Ishmael are involved in digital archiving projects in their own communities. These long-term initiatives, the Martu Project and Mulka Project, ensure that Martu and Yolngu histories and culture are preserved for future generations. As Curtis asks: ‘How can we use this technology to work for us? And for us to use it the way we want to use it? Not technology using us, you know?’ (1) Through their work, Curtis and Ishmael consider these pertinent questions and claim the cinematic space for their stories – their peoples’ stories. Navigating two distinct artistic forms, multimedia and Aboriginal cultural practice, Curtis and Ishmael have found a unique and unified voice that marks a continuation and expression of living culture in the digital age.

Note

(1) Curtis Taylor in CuriousWorks, Mamu: A Directors Vision, retrieved 25 September 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vzfFecoRYng.