Karla Dickens

Lismore, NSW

2017

Displayed 2017 at Carriageworks

Karla Dickens

Born 1967, Sydney. Lives and works Goonellabah, New South Wales

Displaced Wiradjuri woman, Wiradjuri, Southern Riverine region

The driving forces behind Karla Dickens’ need to communicate are her Indigenous (Wiradjuri) heritage, sexuality and life experiences as a single mother. Dickens uses recycled everyday items to explore notions of persistence amid inherent violence and misunderstanding. Made with uncommon rawness and daring, her meticulously fabricated works emanate a rare truthfulness and honesty. Edgy and hard to confine, Dickens often cannibalises existing works to create new ones. She presents a wide-ranging and unique interpretation of the real world, where past and present collide in a multidimensional kaleidoscope of her own making.

Artist text

by Virginia Fraser

Karla Dickens began as a painter, making ‘lots of expressionist work in the nineties at the National Art School’ and, ‘because I had little money, I’d find things to collage’. (1) Later she had a baby, lost another, a friend died. Art seemed ‘self-indulgent’. Then she got an exhibition (2) in Lismore, her hometown, and, using fabric, produced new work that ‘reignited my love’. These deep, dark cloth and paint compositions are still part of Dickens’ visual language, along with sculptural assemblages made in materials including op-shop finds and rurally flavoured hard rubbish and historical refuse from the Lismore tip.

Four decades after the American artist Miriam Schapiro coined the term ‘femmage’ for collage art using material associated with women’s lives, ‘materiality’ is the subject of new discussions in art. Dickens’ work exemplifies both kinds of production, where ‘materials become wilful actors and agents within artistic processes, entangling their audience in a web of connections’, (3) and matter is understood as ‘a dynamic and shifting entanglement of relations, rather than a property of things’. (4) As Dickens puts it:

with the fabric, everyone can relate to it – ‘My aunty had curtains like that!’ It’s kind of familiar, so people get engaged before they realise what’s happening. And I think when you’re opening people’s memory vents you get them at a softer, more vulnerable place.

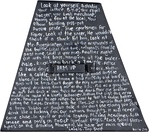

The titles of Dickens’ works Bound (2015) and Fight Club (2016), and her exhibition Black and Blue, (5) say a lot about her hard subject matter – sexualised and racialised violence, deceptions, depression, alcohol-soaked Australian culture, brutal habits and histories. From a distance, Bound’s crowd of empty ink-tinted cloth torsos, with their decorated fronts and long tapering arms, look pretty and somewhat self-deprecating. Close up, they’re straitjackets with multiple buckled straps behind bodices hung with signs of particular bondages – addiction, ideas about femininity, marriage, children, attachment to home, money – reasons women stay in dangerous relationships. One is adorned with cows’ teeth and flowers from 1950s upholstery; homemade greyhound muzzles, clumped hair and sharp fringes of massed combs dangle from others.

Likewise, the eight grouped black paintings of Fight Club might be decorated shields, until you’re near enough to read acerbic poetry on metal rubbish-bin lids.

When his shadow become disconnected,

Peter Pan had Wendy sew it back on

If my shadow went astray, would I search for a needle?

I’m not sure …

My shadow has a richness.

It has colour, depth, its own kind of magic, its special connections.

These paintings are my attempt to give the viewer a peek into the not always black journey of living with the black dog. (6)

Notes

(1) Unless otherwise noted, all quotes are from an interview between the artist and author, 15 October 2016.

(2) Loving Memory (2008) at Lismore Regional Gallery, New South Wales.

(3) Unsigned, ‘Materiality’, overview of Petra Lange-Berndt (ed.), Materiality: documents of contemporary art, Whitechapel Gallery, London, and MIT Press, Massachusetts, 2015, accessed 29 October 2016, https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/materiality.

(4) Karen Barad, Meeting the universe halfway: quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning, Duke University Press, Durham, 2007, p.224.

(5) Presented at Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane, 2016.

(6) Text from the artwork Fight Club #7 (The Black Dog) (2016).