Phaptawan Suwannakudt

Gadigal/Wangal Country, Sydney

2021

Displayed 2021 at Art Gallery of New South Wales

Phaptawan Suwannakudt

Born 1959, Bangkok, Thailand. Lives and works on Gadigal/Wangal Country, Sydney

Phaptawan Suwannakudt trained as a mural painter with her late father Paiboon Suwannakudt and led a team of painters that worked in Buddhist temples throughout Thailand during the 1980s and 90s. In 1996 she moved to Australia and in 2005 completed a MVA at Sydney College of the Arts. Informed by her own sense of displacement she became interested in the idea of translation in art, and often uses Thai script as a visual form. Much of her work has been concerned with the intersection of Buddhism, gender and cross-cultural dialogue. More recently Suwannakudt’s focus has shifted to an exploration of personal narratives within the cultural and political histories of Australia and Thailand.

Photograph: John Clark

Phaptawan Suwannakudt provides an insight into her work in Thai in the following text.

วันนี้คืออนาคตของเมื่อวาน สิ่งที่เราทําาวันนี้คืออดีตและคืออนาคต

สตูดิโอที่ฉันทําางานอยู่ที่ ถนนแอดดิสัน มาริควิลล์ อดีตเคยถูกใช้เป็นที่เกณฑ์เด็กหนุ่มชาวออสเตรเลียและเป็นที่ฝึกรวมพลไปรบสงคราม และเคยเป็นที่ชุมนุมของบรรดาแม่ที่ต่อต้านการส่งลูกๆไปร่วมรบในเวียดนามด้วย

ฉันเติบโตมากับโปสเตอร์เปรียบเทียบคอมมิวนิสต์ในประเทศเพื่อนบ้านว่าเป็นปีศาจร้าย นักศึกษาและประชาชนไทยที่สูญหายและถูกสังหารหมู่ด้วยข้อหาเป็นแนวร่วมคอมมิวนิสต์ ยังไม่มีใครได้รับโทษจากการคร่าชีวิตคนเหล่านั้น

ที่ซิดนีย์มีชุมนุมต่อต้านความรุนแรงของเจ้าหน้าที่เลือกปฏิบัติต่อคนเชื้อสายดั้งเดิมของออสเตรเลียโดยเฉพาะคนรุ่นเยาว์ที่ไม่มีทางสู้ ที่เมืองไทยมีการชุมนุมเรียกร้องแก้ไขรัฐธรรมนูญซึ่งต่อมาขยายประเด็นเป็นวงกว้าง ภาพเด็กนักเรียนมัธยมที่พยายามปิดบังสถานะตัวตนของตัวเองระหว่างประท้วง และเพลงแสงดาวแห่งศรัทธา โดย จิตร ภูมิศักดิ์ ถูกรื้อฟื้นมาร้องในที่ชุมนุม

งานชุดนี้เสนอทรงจําาในเวลาคู่ขนานสถานที่ทั้งสองของชีวิตฉัน

Artist text

by Natalie Seiz

‘Silence was always the solution.’ (1)

Phaptawan Suwannakudt has lived in Australia for 25 years after immigrating from Thailand in 1996. I remember the first time I met Phaptawan, who had just had a baby daughter and was living in a unit in Sydney with her partner. One of the first works she produced after arriving in Australia was Lives of the Buddha (1997–98). She was so limited by her living space that she had to paint the work in sections on separate canvas frames – a far cry from the large wall murals she created while living and working in Thailand.

Much of Suwannakudt’s work has dealt with her memories of Thailand and her encounter with Australia. The birth of her children inspired her to again question different aspects of her life: where was home for them? Where was home for her? Always quietly spoken, I have observed Suwannakudt over the last few years as she has discovered her own voice in an Australian cultural context, where the loudest voice often seems to be the only voice considered. Stating one’s opinion can be difficult for someone like Suwannakudt, who has lived under a military regime that discouraged an activist voice, especially the voice of a woman.

The year 2020 was significant in many ways, one being the ascendency of the Black Lives Matter movement worldwide, which advocated permission to embrace my colour, my cultural heritage, myself. Part of the fear in speaking out dissipated, in the knowledge now that other people felt the same way. Perhaps this realisation motivated Suwannakudt to create such a challenging work. 2020 began in Thailand with students protesting for government reform and it was the first time the lèse majesté (insult of the monarch) laws were openly challenged. It is in this context that Suwannakudt has engaged in questions about Thailand’s politics and the freedom of its people.

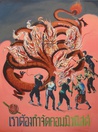

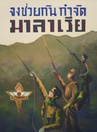

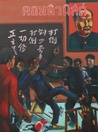

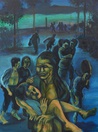

RE al-Re-g(l)ory (2021) are paintings of Thai government propaganda posters, the likes of which surrounded Suwannakudt when she was growing up in Thailand in the 1960s and 70s. They were part of an anti-communist campaign that the Thai government promoted, which was most likely funded by the United States Information Service, who had a presence in Thailand at the time. (2) The posters are often a comparison between a perceived good versus evil. One side, called Communist, depicts what life could be like under communist rule; the other, Free State, shows life under ‘democracy’, in other words – Thai monarchical military rule.

The recontextualisation of these posters in Suwannakudt’s new work brings with it a renewed understanding of what they meant at the time and how we read them today. Their didactic appeal was especially targeted at Thais who were unable to read. In RE al-Re-g(l)ory, the intensity of the posters is tempered by the blank white boards dispersed throughout the work. They represent the A4 sheets of paper that have since been carried by student protesters as a reminder of the silencing, disappearance and death of innocent people during the political coups pervasive during the 20th and 21st centuries in Thailand. They are a reminder that words do not necessarily convey the strongest sentiment.

(1) Phaptawan Suwannakudt, Notes provided by the artist, 2020.

(2) Michael Rattanasengchanh, ‘US–Thai public diplomacy: The beginnings of a Military-Monarchical-Anti-Communist State, 1957–1963’, The Journal of American–East Asian Relations, no.23, 2016, pp.56–87.