Robert Fielding

Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara Country, Mimili, South Australia

2023

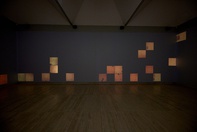

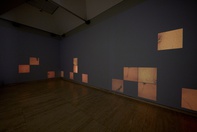

Displayed 2023 at Art Gallery of New South Wales

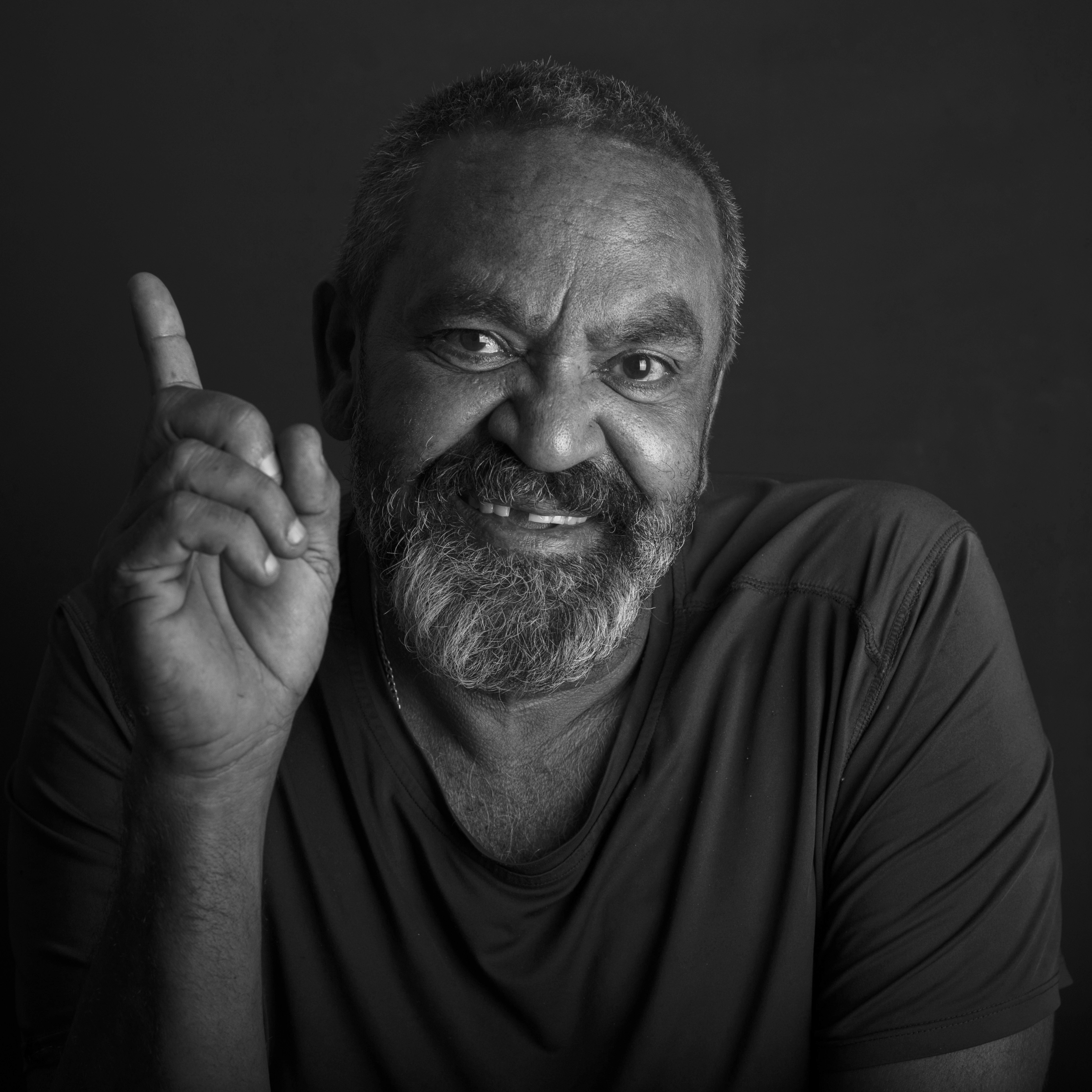

Robert Fielding

Yankunytjatjara/Western Arrernte peoples; Pakistani/Afghan descent.

Born 1969, Kokatha Country, Kurdnatta/Port Augusta, South Australia.

Lives and works Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara Country, Mimili, South Australia.

Combining strong cultural roots with contemporary perspectives, Robert Fielding’s practice spans photography, works on paper, sculpture, film, and installation. He articulates a unique connection between his people and the earth, exploring what it means as an Aboriginal person to hold millennia of knowledge within Country. Fielding explains, ‘Our people, our spirit, our languages, our song and dance are all expressions of the sacredness of this earth. This sacredness radiates through my Elders, in everything they do, everything they are, everything they create … My work is a reminder of that sacred interconnectedness, miil-miilpa.’

Photograph: Meg Hansen

Artist text

by Erin Vink

Robert Fielding first introduced me to the term ‘milpatjunanyi’ in 2020. At the time, we were working on Wirura kanyini (2020), a lockdown project that explored the stories of past, present, and future Mimili. In the simplest of terms, milpatjunanyi is a thriving cultural practice that can be understood as the marking of the earth with a stick or wire for storytelling. Milpatjunanyi frames all visual depictions of Country, experience, language, song, and dance in tangible ways. Milpatjunanyi is the multiple forms in which stories can be told.

Milpatjunanyi is a practice often associated with women’s storytelling: from the recounting of stories that are eternally present and held within the manta (earth) through to the practice of using art to recall day-to-day lived experience. Captured in high definition, milpatjunanyi is presented by Robert Fielding in Milpatjunanyi (2022), and features storytelling by Ngilan Dodd, Tuppy Goodwin, Betty Pumani, Umatji Tjapalyi, Pauline Wangin, Puna Yanima, and many other Mimili community members. Fielding has constructed what he calls a field of ‘loops,’ or single frames that are grouped into grids of four, where the storytellers’ voices bleed into and over one another, and where the marking of Country unfolds across this installation in a non-linear way.

Watching this work, born from two earlier short films titled Milpatjunanyi (2020) and Manta (2020) – both included in Wirura kanyini – I can appreciate what Fielding meant when he told me that ‘stories are eternal. (1)’ This act of milpatjunanyi has been perfectly preserved, and within these moments of storytelling, where gentle and graceful hands enter the bottom and sides of frames here and there, I can listen and watch, and begin to understand these knowledge-holders. I can understand what they have taught, what they have restored, who they have sung to, who they have danced with, and what words they have spoken. I see Country through Fielding’s and their eyes, including recollections from an entirely different time.

It is the number one priority of Anangu to hold onto the stories of their communities and so, when sitting down to mark the manta, the storyteller, or ‘conductor,’ would be held in high regard. In control, they hit the earth with authority, manoeuvring the stick or wire through Country and to a precise choreography. It is important to recognise that Fielding, like his Anangu contemporaries, has moved into new modes of storytelling, be that through canvas, photography, or installation, but still at the core of his practice is the inherent desire to hold on to and to defend story and Tjukurpa, so that it can remain in Country for a lifetime.

In 2020, I wrote that Fielding’s art on milpatjunanyi was about ‘bringing a snippet of manta to the uru (ocean) and back again (2),’ and this is certainly true for this new work. For Anangu and Fielding, stories are eternal, held on to, or given away. They can exist long-term within tangible forms like this film, or within the sand for a fleeting moment only. Regardless of medium, Fielding teaches us that our stories go deeper than us, held within the manta, where we will find ourselves intertwining with them again and again.

(1) Robert Fielding, artist statement supplied to the author for ‘Wirura kanyini’, 26 June 2020, https://togetherinart.org/robert_fielding/

(2) Erin Vink, ‘Wirura kanyini (well looked after)’, 13 July 2020, https://togetherinart.org/robert-fielding-well-looked-after/

Artist's acknowledgements

Robert Fielding gives his gratitude to all participants, knowledge-keepers and storytellers past and present involved in this project. All storylines shared in this work belong to Yankunytjatjara Country and have been kept strong by countless generations of Elders and Ancestors who have nurtured and lived them through their knowledge, culture, and language.

The artists and Mimili Maku Arts thank Erin Vink, Cara Pinchbeck, Coby Edgar, and Beatrice Gralton for their ongoing support of Aboriginal-owned art centres, and for their belief in the importance of our work. Mimili Maku Arts also thanks the Indigenous Visual Arts Industry Support program for their ongoing investment to support Anangu employment as part of our business. Robert Fielding furthermore acknowledges the support received through the Australia Council for the Arts over the course of his career.

Collaborators: Ngilan Margaret Dodd, Ngintja Tuppy Goodwin, Betty Kuntiwa Pumani, Marina Pumani Brown, Tanya Umatji Tjapalyi, Pauline Wangin Minmila, Emma Singer, Betty Campbell, Puna Yanima, Beverly Downs, Sheena Dodd, Kathy Dodd, Patricia Martin, Betty Mula, Josina Nyarpingku Pumani, Anita Pumani, Amy Yilpi, Joanne Tjili Wintjin, and Rhonda Young.

Robert Fielding is represented by Mimili Maku Arts, South Australia.